The contract that wasn't

The contract that wasn't

GPs in Northern Ireland thought they had a deal. But money to cover indemnity costs was clawed back and funding remains woefully inadequate. Jennifer Trueland hears from GPs about the overwhelming support for collective action

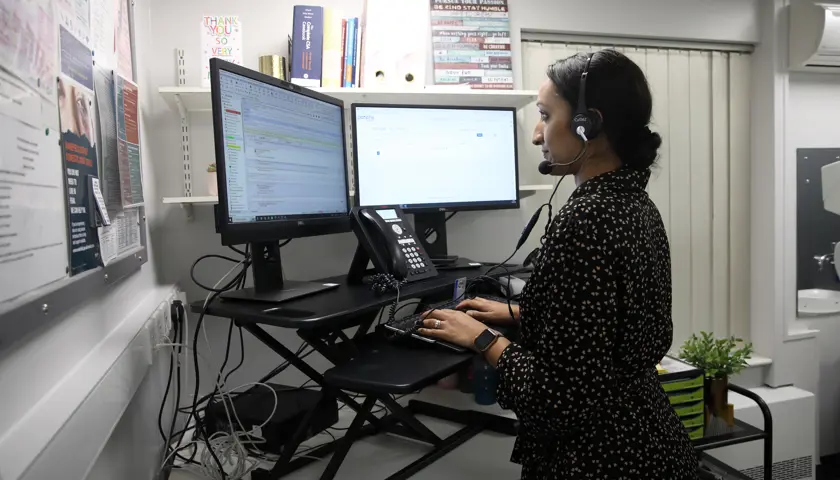

When Frances O’Hagan (pictured above) took over as chair of the BMA Northern Ireland GPs committee last July, she – and almost everyone else – was under the impression that a contract for 2024-25 had been agreed. Given the difficult financial circumstances in Northern Ireland, it didn’t look too terrible a deal.

Importantly, it included money to pay for indemnity cover, correcting an imbalance which sees GPs in Northern Ireland as the only ones in the UK to be out of pocket to meet this essential cost. However, it soon emerged this wasn’t exactly the case.

‘It became apparent that what we believed we had negotiated was not what the other side was enacting,’ says Dr O’Hagan. ‘We thought we’d agreed £5m for indemnity, which was paid upfront, but then it was taken back through clawbacks. It was a great disappointment for us, and it led to uproar in the profession.’

The anger and disappointment had consequences. Since the end of July, GP partners across Northern Ireland have been taking collective action, including limiting the numbers of consultations they do in a day, and refusing to complete unfunded paperwork.

'Simple equation'

It’s not just about indemnity costs, explains Dr O’Hagan, speaking to The Doctor magazine at the practice in Armagh where she is senior partner. It’s also about the urgent need for more investment in core general practice.

This is absolutely not about more money for GPs themselves, she stresses. ‘We’ve never yet asked for a pay rise – we asked for it so that we could employ more receptionists, more nurses, and more doctors, because we’re being hammered all the time and told “we need more access, we need more access”. And we’ve said we can’t provide more access unless you give us more staff to answer phones and more staff to see the patients. It’s a fairly simple equation.’

The BMA’s ‘ask’ was for £39 per patient, per year, which works out at around £80m. It would form part of a rebalancing whereby a greater slice of healthcare funding would come to primary care. ‘When I first started in general practice, we were getting about 10 per cent of the [health] budget for doing 90 per cent of the contacts. We’re still doing 90 per cent of the contacts but now we’re getting 5.4 per cent of the budget.

‘We asked for £39 per patient to give more access, but they offered us £1m, which is 50p per patient per year, less than a penny a week. And for that £1m we have to jump through about 17 different admin hoops, none of which will actually provide a single extra appointment.’

We've never yet asked for a pay rise – we asked for [funding] so that we could employ more receptionists, more nurses, and more doctors

Frances O'Hagan

When the BMA asked the profession back in May of this year what they thought of this offer, the results were unequivocal. Around three-quarters of GPs on the register in Northern Ireland responded, with 99 per cent saying that the offer wasn’t enough to keep the lights on or the doors open, says Dr O’Hagan. GP partners were then asked if they wanted to take collective action – and they answered yes – being self-employed, GP partners can’t strike, but they can take collective action.

Meanwhile, health minister Mike Nesbitt came out fighting saying it was a ‘matter of regret’ that agreement hadn’t been reached with GPs, but reiterating that financial challenges meant that it wasn’t possible to offer any more.

‘It shows just how bad things have got here that we’ve got GPs on board for collective action, because previously people would have done anything and gone to any lengths to help patients out, even if it wasn’t their responsibility to do it,’ says Dr O’Hagan.

In Dr O’Hagan’s practice, the collective action has helped bring home to them just how much unfunded work they were doing – for example, providing sick notes for patients who have been discharged from hospital (before the discharge notification has even reached the practice), or organising transport for people attending hospital.

And her practice is not alone in this. Conor Moore is a GP partner in the neighbouring Abbey Court Surgery (in fact they share a site) in Armagh.

‘There are a number of GP practices returning to the trust patients who need complex wound dressings and bloods for hospital clinics. These aren’t funded to be done here but there’s a huge lot of work being done in our treatment rooms, which is unfunded, and is blocking access to appointments for patients who need bloods done so that we can investigate them properly,’ he says.

‘We’re trying to push back,’ says Dr O’Hagan. ‘For example, if you break your leg and get a plaster on, frequently we don’t find out for ages, and they should get a line from the fracture clinic to say they’ve got a plaster on for six weeks, but they don’t. Or if you go in and have your gall bladder out, I’m not a surgeon so I can’t recommend the length of time I think you should be off work for that.’

The big issue, says Dr Moore, is that dealing with all these queries blocks access for patients looking for actual services funded within core general practice. ‘At 8.30 in the morning there’s 10 people on the phone looking for a letter that should have been issued somewhere else, then that’s blocking people’s access to a call back and an appointment. For a [health] department that prioritises access, you’d expect them to put a wee bit more effort into making sure that other areas of the health system are doing the things they should be doing.’

Huge mandate

Most of the collective action doesn’t involve patients directly, says Dr O’Hagan. Rather, it’s largely bureaucratic requirements from the BSO (Business Services Organisation) part of the Health and Social Care System, such as using medications optimisation software, which can add hours to the already onerous task of completing repeat prescription requests (which are still done manually in Northern Ireland). But although this means she is ‘not on anyone’s Christmas card list’ at the BSO, it’s the interactions with patients that’s the hardest bit.

‘The issue is that we know them and they know us, so it’s a real tug at the heartstrings,’ she says. ‘We want to help our patients out, we don’t want to fall out with them. But there’s a realisation now that there’s no capacity left in the system. The fact that we have such a big mandate for collective action shows that morale is low, but the strength of feeling is so high in the profession at the minute, that we’re prepared to have these difficult conversations with patients and the public now in order to try to make things better overall.’

A number of mid-career GPs like myself are maybe down to one day a week because they can't cope with the stress of the job any more

Conor Moore

Dr Moore agrees it is hard to share that with patients. ‘I mean, it’s very easy to say yes, and it’s very difficult to say no, and I think a lot of practices feel like that. We are probably the easiest part of the health system to access in terms of getting through to that high-level professional and getting an answer. So, when someone is refused a Med 3 [statement of fitness for work] and is sent back to hospital and can’t get it, they will come repeatedly back to us, which takes an awful lot of time and chokes up the system even more.’

It is no wonder it feels easier just to do it – but this is counter-productive in the long term, adds Dr Moore. ‘It’s also easier for the patient if we just do it, because we don’t want to put them in that position. But until we actually take action and make sure that the system starts to take responsibility for what it should be doing, the patient will continue to get stuck in the middle, and that’s the difficulty we face.’

Not being able to do the job they want to do is affecting individuals and is a threat to the future of general practice, Dr Moore stresses. ‘I had my 20-year graduation reunion recently, and a number of mid-career GPs like myself are maybe down to one day a week now because they can’t cope with the stress of the job any more. A number of people in my training have moved aside into associate specialist jobs within hospitals. They’re not doing general practice any more and it’s really hanging by a thread. There’s also a lot of talk about private care and leaving the NHS altogether. This is a real worry.’