The exam question

The exam question

When it’s mandatory to take postgraduate exams, why does the cost fall on doctors already suffering from years of pay erosion?

‘One day when I got home after a 13-hour shift in an intensive care unit and my meter said I had only spent 50p on electricity I noticed I was genuinely happy about that. It was because I had to pay for my exam the next month.

‘Then I stopped myself, and I thought “this is absolutely ridiculous”.’

Hampshire internal medicine trainee 2 Lucie Olivova gives a window into the financial pressures faced by doctors in specialty training – pressures which have only intensified through years of pay erosion and the cost-of-living crisis.

It has long been the case doctors have had to pay for the privilege of progressing in their careers but Dr Olivova is among a growing group asking if it must. Mandatory costs also come in the form of medical royal college membership subscriptions, GMC fees and medical indemnity, but perhaps sting the most when it comes to specialty training.

Fees, typically hundreds but up to thousands of pounds per exam, have remained stubbornly high despite doctors’ real-terms pay eroding for 15 years. In the meantime, other professional perks such as accommodation and car parking now come at a cost and student-loan debt has rocketed for recent graduates.

It’s not up to me whether I want to do an exam or not, it is a mandatory requirement of my programme

Lucie Olivova

With the cost of being a doctor – of going to work – biting a large hole in already meagre pay packets, the BMA passed policy at its annual representative meeting last year calling for mandatory fees to be reimbursed by employers, as they are in comparably high-skilled professions.

Dr Olivova, an IMG (international medical graduate) from Czechia, training in dermatology, says she ‘just couldn’t understand’ why mandatory exams and portfolios are expected to be the financial responsibility of employees when they are essential to training for the roles employers need.

‘It’s not up to me whether I want to do an exam or not, it is a mandatory requirement of my programme – I don’t make the rules,’ she says. ‘I’ll fail my programme if I don’t do the exam. Plus, I have to study outside work hours. I shouldn’t have to pay for the extra work I need to do.’

'Overwhelming' costs

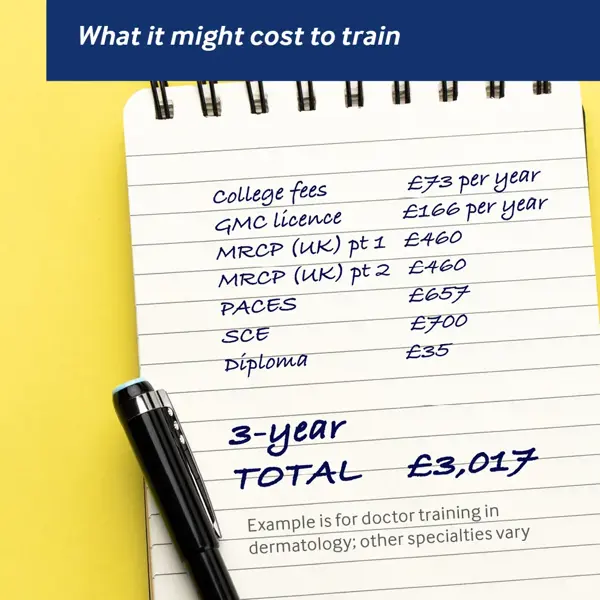

Exam fees vary by specialty. Dr Olivova paid the Federation of Royal Colleges of Physicians £460 each for parts one and two of the MRCP(UK) and £657 for her PACES exam.

Those costs are as well as portfolio fees of £516 to £860 a year. Once she completes her MRCP(UK) exams Dr Olivova faces another £700 to take an SCE (specialty certificate examination) in dermatology. Non-fellows must also pay £35 for their diploma to be delivered.

And with low pass rates for specialty exams, many doctors face costs more than once if they take resits. All that is on top of medical royal college fees (£73 per year for IMTs such as Dr Olivova or £146 for specialty trainees), and £166 a year to retain a GMC licence to practise, plus medical indemnity which typically costs hundreds a year.

For three years of training, exam costs alone will surpass £2,000. Payments cannot be spread using direct debits, but doctors can reclaim tax.

‘I’m not able to save much because I have financial commitments back home, plus rent, electricity and other bills,’ says Dr Olivova, who notes other ‘unpredictable life expenses’ also crop up, such as car maintenance, which last year cost her £1,300. ‘Because I need to drive to work, I had to just deal with it. It was quite disheartening,’ she says.

‘Going through my [first two] exams, which were three months apart, I needed to spend my savings on exams, textbooks, question banks, and all those other costs. It was quite overwhelming.’

Oba Babs-Osibodu, co-chair of the BMA Welsh junior doctors committee, says that while most aspiring doctors are aware they must pay for postgraduate exams, the ‘ridiculously expensive’ costs ‘especially compared to pay’ do not become clear for many until they embark on specialty training programmes.

Radiology specialty trainee 2 Dr Babs-Osibodu has completed the anatomy and physics exams for part 1 of his FRCR which cost him £319 each (RCR now quotes £357 to £389) and has booked part 2A at £478 (it can cost up to £521). Part 2B is priced at £669 to £728. To undertake specialist radiology training, candidates must be members of the RCR, which costs £299 a year as a trainee and includes access to an ePortfolio.

‘It’s an onslaught,’ says Dr Babs-Osibodu. ‘There are always fees. When I became an ST2 I got a bit of pay increase. Then, when I was trying to get a bit more comfortable, I was hit with this massive cost.

‘When I’m paying for exams, I’m thinking, “how much money am I going to have left?”.

‘The people employing and training me shouldn’t be making life harder, they should be trying to encourage and help my progression and training. It doesn’t feel like that.’

Dr Babs-Osibodu contrasts the situation with friends working in other sectors: ‘Their employers are paying for them to go on courses and study for exams which are not even necessarily mandatory. They want to get the best out of their potential, whereas for us it almost feels like blackmail. It’s like, you either pay us or you’re out [of specialty training].’

They should be trying to encourage and help my progression and training. It doesn’t feel like that

Dr Babs-Osibodu

London GP Gerard McHale retrained as a doctor after a career in accountancy and concurs with Dr Babs-Osibodu’s assessment.

During his three-year post-graduate accountancy training, Dr McHale earned a master’s degree and became a chartered accountant. All exam costs were paid by his accountancy firm and he was given paid study leave. His firm also paid membership of his professional body, the Institute of Chartered Accountants, the equivalent of covering a doctor’s GMC and medical royal college fees.

By contrast, GP trainees pay £470 for their AKT (applied knowledge test) and, from 2023, £1,180 for the new SCA (simulated consultation assessment), which replaces the £1,076 RCA (recorded consultation assessment) that was brought in during COVID to offer a remote alternative to the CSA (clinical skills assessment), which had cost £1,352. If trainees join the Royal College of GPs as an AiT (associate in training), they don’t pay portfolio costs. Subscription costs are £423 a year if training full-time, plus a £291 registration fee (reduced to £73 at certain times of year).

'Paying for the privilege'

In the accountancy sector, it is ‘taken for granted’ that firms cover exam fees and professional development, says Dr McHale. ‘The rationale is that they get the benefit. As you get more experienced, you can do more. But that’s the same in healthcare; as you get more experienced you take on more responsibility and provide a higher level of care. The employer, in both cases, gets more from you, and to do more you need the extra training.’

Dr McHale says justification in medicine for asking employees to cover costs is often that doctors get paid more after completing specialty training.

That means doctors are ‘paying for the privilege’, which ‘shouldn’t be the case’, while in professional services exam costs are seen as ‘part of the package’, he says.

Nottingham psychiatry trainee Alice Ogunji paid more than £500 to take her MRCPsych Paper A. At the first attempt, she missed out on a pass by 0.8 per cent, meaning she had to pay again to resit the exam, which she passed just before Christmas.

The small margin for the first attempt was made even more frustrating because her preparation was interrupted when she received an email at 7pm the night before to tell her the exam had been moved to Derby from Nottingham, meaning she had to find – and pay for – a last-minute hotel.

Core trainee 2 Dr Ogunji will have to pay £496 to take her MRCPsych Paper B and £1,096 for her CASC exam. They are the reduced fees she pays as a RCPsych pre-membership psychiatry trainee, which she pays £158 a year for.

The latest pass rates for the MRCPsych Paper A were 62 per cent; Paper B had pass rates of 43 per cent; and the CASC 50 per cent. The MRCP Part 1 had three sittings in 2023, with pass rates ranging from 41 to 53 per cent; Part 2 ranged from 64 to 73 per cent; and PACES between 49 and 64 per cent.

Dr Ogunji says the low pass rates indicate that exams are set at the wrong level. She has run ‘irrelevant’ sample questions past clinical supervisors, who she says rarely get many right.

Dr Olivova agrees: ‘A lot of questions don’t seem relevant to the way we actually practise medicine. The questions are way too theoretical and often become completely unrealistic.’

She says this is ‘especially important in the context of today’, when debate rages about the regulation and pay levels of medical associate professionals, who are not trained to the same level as doctors but are increasingly reported to be taking on responsibility beyond their scope.

Dr Olivova asks: ‘How are we putting doctors through exams so rigorous and theoretical that we have to spend hours of our free time every day for two to three months to prepare for them, to then go back to work and see that none of this knowledge seems to be relevant?’

Evidence also shows lower pass rates among international medical graduates, who make up an increasing proportion of the NHS’s medical workforce.

The MRCP(UK) 2022 equality and diversity report shows 69 per cent of UK-trained doctors passed MRCP part 1, versus 51 per cent for IMGs. This was 78 vs 62 per cent for part 2, 69 vs 43 per cent for PACES and 73 vs 44 per cent for the SCA.

RCGP results also vary in data based on exams taken since 2014. For the AKT, 83 per cent of UK graduates passed compared with 46 per cent of IMGs; in the CSA 90 per cent of UK graduates passed compared with 44 per cent of IMGs, and for the RCA this was 92 per cent against 50 per cent.

Doctors were also more likely to pass if they are white than BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic), and if they are female.

Psychological harm

Orthopaedic surgeon and hand and wrist surgery fellow Simon Fleming, who has a PhD in medical education, noted the ‘increasing evidence’ that specialty exams are discriminatory, and that doctors sitting them face the ‘psychological harm of having to withdraw from family, friends and life’ to become ‘some kind of exam hermit for a year or more’.

He says pass rates are ‘evidence of a suboptimal training system, a flawed assessment model or both’ and that the length of time doctors spend studying to try and pass is a ‘sad indictment’ of the system.

Mr Fleming agrees ‘most consultants’ concede they would not pass the exam, especially the written components, without intense prolonged study and ‘even openly say things like “you learn it so you can forget it”.’

While he says medical royal colleges’ income from exams ‘cannot be ignored’, he notes the ‘narrative cuts both ways’ as those who design and run the exams ‘often do so in their own time, without remuneration or recognition’ and colleges set high standards for safety reasons.

Mr Fleming backs moving to a longitudinal programmatic system of regular ‘low- to medium-stake’ tests during training using a combination of more robustly done workplace assessment and potentially outside observation to create a ‘contextual, comprehensive and relevant’ postgraduate experience. ‘It is time for us to re-examine exams,’ he says.

A motion passed at the BMA’s 2023 ARM in Liverpool acknowledged the financial burden of medical training on junior doctors, calling on the BMA to demand relevant bodies reimburse fees.

It says the first attempts of any mandatory exams should be covered, along with any mandatory portfolio costs. For subsequent attempts, it asks for 50 per cent of the exam cost to be reimbursed.

Dr Olivova, who wrote the motion with Dr Ogunji, said the ask is ‘realistic’ but says the ideal solution would be that doctors do not pay at all. Fees, she says, should be covered out of trusts’ study budgets, which HEE (Health Education England) recently agreed to fund centrally. However, current HEE guidance states that, while study budgets can cover courses to help prepare doctors for post-graduate exams, they cannot cover exam costs, portfolios or medical royal college membership fees.

Pass rates are evidence of a suboptimal training system, a flawed assessment model, or both

Mr Fleming

HEE says changing this would be a decision for the Government’s Department of Health and Social Care. A spokesperson says the DHSC is ‘committed to ensuring that postgraduate doctors in training have the financial support they need’ and ‘continues to keep the impact of exam costs on those doctors under review’.

Drs Olivova and Ogunji reported a ‘postcode lottery’ with current study budgets. Some trusts offer to pay doctors’ travel and accommodation costs when they’re sitting exams, but not all. They believe more doctors in specialty training would value spending the money on mandatory exams than non-essential career progression courses, which they suggest can be covered if any budget remains.

Doctors also argue medical royal colleges could charge less in exam fees, especially now many have moved online since COVID. But colleges insist they are not using exam fees as an income stream, and only charge enough to cover their costs.

A recent report by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges’ Trainee Doctors’ Group finds ‘significant financial pressures for trainees in terms of financing study materials, training and revision courses, and examination fees’.

It says: ‘Examination fees in particular have been a perennial issue for doctors in training and with the UK in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis several trainees report they are unable to undertake these exams owing to financial pressures, inhibiting their progression.’

It adds that the number of trainees affected ‘is likely to increase, even after the cost-of-living crisis is over’ and this ‘puts increasing pressure on candidates which can impact both their wellbeing and even their examination success’.

The report also notes ‘increasing numbers of trainees are choosing to leave their training pathways’ with financial pressures ‘one of the contributing factors’.

It recommends government, statutory education bodies or other relevant organisations consider paying for the first attempt of such ‘high-stakes’ mandatory exams in the postgraduate medical specialty training pathway across specialties and that stakeholders ‘explore the use of the trainee study budget to fund examination fees’, and the potential of paying in instalments.

And there is a precedent. In Wales, GP and psychiatry trainees have their first exam attempts paid for by the Welsh Government’s ‘Train.Work.Live’ scheme.

Justifying costs

The RCGP says it runs exams on a ‘cost-neutral basis over a three-year cycle’. It also publishes a breakdown of its topline costs, which stretch into the millions, and notes for example the expense of paying for locums to cover examiners (who are practising GPs). It says doctors no longer have to cover travel and accommodation costs for its now-remote SCA exam.

It also notes the ‘financial hardship’ GP trainees experience in its 2022-23 exam costs explainer, adding: ‘The college should not use the MRCGP as a source of income to fund other college activity.’

Margaret Ikpoh, vice chair of the RCGP, says: ‘The purpose of the MRCGP assessment is to ensure patient safety and that GPs meet the standards necessary to practise independently and safely as GPs in the UK.’

A 2013 judicial review of the MRCGP exam found it was ‘lawful and fair’ and a 2017 independent review of the then-CSA and AKT said they were fit for purpose.

Dr Ikpoh says the college ‘has always been transparent about differential pass rates’ and is ‘committed to identifying and addressing the underlying issues’, adding: ‘If we are to truly address differential attainment, we need to focus on much wider factors than the examination.’

If we are to truly address differential attainment, we need to focus on much wider factors than the examination

Dr Ikpoh

The RCPsych breaks down its costs on its website, up to 2021, and says exams would be hundreds of pounds more if they had been pegged to consumer prices index inflation between 2012 and 2021. In that nine-year period, they dropped by more than £300 but have since returned to 2012 levels. It says fees ‘should not be set to generate significant surpluses’ and any surplus of more than 10 per cent will be diverted into its trainees fund.

RCPsych Dean Subodh Dave says ‘rigorous quality assurance’ ensures ‘exam questions are meticulously reviewed and discussed for fairness, reliability and validity’ and that measures including accessible use of language and diversity on panels protects candidates against ‘any risk of bias’.

He says the college understands ‘the economic outlook is difficult right now’ adding that exam fees are ‘regularly reviewed’ to make them ‘more manageable’ – but warned funding first attempts could create additional costs for other members. The college offers bursaries and award schemes and has frozen trainee subscription fees for 2024.

Dr Dave says the RCPsych ‘would welcome further discussion on whether NHS organisations or health education bodies could use their allocated funds for training to pay for trainees’ exams’.

'Regular reviews'

The Federation of Royal Colleges of Physicians has held fees for its exams for seven years and says income is used to cover costs such as clinicians’ time for setting questions, quality assurance, reviewing outcomes, facilities, IT and improvements.

It says it ‘would be happy to be involved in any discussions’ about how doctors can be supported with their post-graduate exam fees.

The federation said all MRCP(UK) examinations are set using internationally accepted methodology, ‘with preservation of patient safety central’ and that the ‘phenomenon’ of differential attainment is present across all postgraduate medicine examinations. It makes its pass rates public and shares its equality, diversity and inclusion action plan online.

The RCR says its exam fees have not even covered its own costs in recent years and it ‘regularly reviews’ pass rates and curriculum.

‘Our exams are challenging but no more challenging than they need to be,’ a spokesperson says. ‘We continue to review and improve the delivery of our exams to ensure value for members and maintain high professional standards.’

The GMC’s 2023 workforce report found a growing proportion of doctors taking an increasing amount of time away from training after foundation year 2. The main reasons cited include readdressing work-life balance, preventing burnout and taking a break from exams and portfolio work.

Dr McHale believes the debate ‘comes down to how much you value your employees’ and says covering mandatory training costs has ‘been customary in many other professions for 20 to 30 years’.

Dr Olivova says exam costs, in the context of pay erosion, is ‘another example of the social contract we signed up to when we went into medicine being broken’. She says when she questioned the system she received a ‘long and very well-written email’ reply from her programme director who ‘basically said, “it is what it is and it’s the same everywhere”.

‘This is one of those conversations you have in doctors’ messes over and over and everybody keeps saying “it’s stupid, it’s ridiculous” but also end with “it is what it is”.

‘I really don’t think we should accept that.’

- Until September 2024, resident doctors were referred to as ‘junior doctors’ by the BMA. Articles written prior to this date reflect the terminology then in use