Heal at home

Heal at home

An increasing number of patients are avoiding hospital admissions and long stays through being monitored on ‘virtual wards’ at home. Ben Ireland finds out how they work

‘It's been much easier,’ says 79-year-old Stephen Kaye, who has Parkinson’s Disease. ‘I feel more comfortable at home.’

Mr Kaye’s wife and carer Jillian recalls how being told her husband would be able to go home so soon after being admitted to hospital initially gave her ‘the collywobbles’.

He had previously spent 19 days at Watford General Hospital being treated for pneumonia before discharge, and after 10 days at home was readmitted for a fall and urine infection. This time, he was offered early supported discharge on the Hospital at Home pathway – a virtual ward run by CLCH (Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust).

Mrs Kaye tells The Doctor: ‘I was tearful, I thought there was no way I was going to cope when he’d had a whole team looking after him. I was petrified, I didn’t sleep and couldn’t see how it was going to work. But they said it would be safer at home and they were right. It’s worked brilliantly.’

She describes a ‘mindset change’ and ‘learning curve’ where she gradually became more comfortable with hospital-level care taking place in their home in Hertfordshire.

At home, Mr Kaye – who also has prostate cancer – is more mobile than he was in hospital. He spends less time in bed and has more home-cooked meals.

His observations and interventions are conducted by nurses and physios who make regular visits, and Mrs Kaye is pleased to know extra advice is just a phone call away, and that treatment can be escalated if needs be.

The family is looking ahead to Mr Kaye’s 80th birthday party in November and hope to go on a cruise holiday. ‘Anything is better than being in hospital,’ says Mrs Kaye. ‘The care there was great, but he’s home now.’

Remote monitoring

The intention of virtual wards is two-fold: to reduce the number of patients admitted to hospital and allow more patients to reduce their lengths of stay through safe, early supported discharge. The service is for patients who would otherwise be in acute hospital beds, and typically cares for them for up to two weeks.

Patients, usually older and frail, receive hospital-level care in their homes, enabled by remote monitoring technology including SATS probes worn on the finger and ESG monitors.

Common conditions include COPD, heart failure and dementia. Palliative care can be offered when appropriate.

Patients are cared for by multidisciplinary teams, with either a consultant or GP-level doctor overseeing from a remote hub.

For West Hertfordshire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, this is based at Watford General Hospital and led by consultant cardiologist Niall Keenan. They work together with the community team from CLCH, led by the trust’s deputy chief medical officer, complex care GP John Rochford. Virtual wards were rolled out widely at the height of the pandemic for COVID patients but have since been adapted to treat more conditions.

Dr Rochford had been aware of an early initiative in Oxford and recalls: ‘What really struck me was the technology that was bubbling up. We saw you can do bloods at the bedside, you can remote monitor more easily, all these things which allow community practitioners to do more with patients at home.

The care in hospital was great, but he’s home now

Jillian Kaye

‘Given the pandemic was pushing for people to be managed at home and not come in to hospital, I decided we needed to look at this and train our teams to give them the skills, free up hospital beds and do right by our patients. Barriers that previously existed seemed to go away more easily so we could get things done at pace.’

In Watford, Dr Keenan says ‘circumstances forced innovation’ as the number of COVID patients began to recede.

‘We thought other patients could benefit,’ he adds, explaining how the team focused on COPD and heart failure patients before expanding into other pathways.

NHS England is keen on the idea, too. Its Long Term Workforce Plan includes an ambition to provide 40-50 virtual ward beds per 100,000 population, which would mean about 25,000 beds in England. An initial target to have 10,000 virtual ward beds before this winter was met ahead of schedule – with more than 240,000 patients treated on virtual wards by October 2023.

NHS Providers head of policy and strategy David Williams says virtual wards are ‘often better for people’s recovery’ and ‘can help relieve pressure on the NHS by freeing up hospital beds for those who need them most’.

That said, he warns they are ‘no magic bullet’ and highlights the need to address workforce shortages and invest in technology to enable the model, with public and staff buy-in also ‘key’.

The NHS Confederation records how many beds are ‘filled with patients no longer meeting the criteria to reside in hospital’, with an average of 13,776 such beds a day in the week commencing 5 February and similar numbers throughout winter. The National Audit Office estimates the NHS spends £820m caring for older patients in hospital beds who are no longer in need of acute treatment.

As of January 2024, West Hertfordshire’s acute virtual hospital had cared for about 1,800 patients – with roughly two thirds given early supported discharge and the other third avoiding admittance to hospital.

And up to January, virtual wards at CLCH had supported 3,138 patients; more than three quarters on early supported discharge. According to the trust’s modelling, it had saved 9,136 acute hospital bed days through early supported discharge.

Doctors at both trusts stress the virtual ward model has been set up to ‘do right by patients’ by reducing the risk of deconditioning or picking up viruses — and is based on evidence which shows better outcomes for older adults whose discharge is not delayed.

Studies have shown that mortality in patients aged 85 and over admitted to hospital with acute illness approaches 50 per cent at one year, five times higher than patients under 60 years of age.

‘Holistic care’

Trusts say patient feedback has been positive, too. ‘Hospital doctors sometimes massively underestimate what it means to a patient to be at home,’ says Dr Keenan.

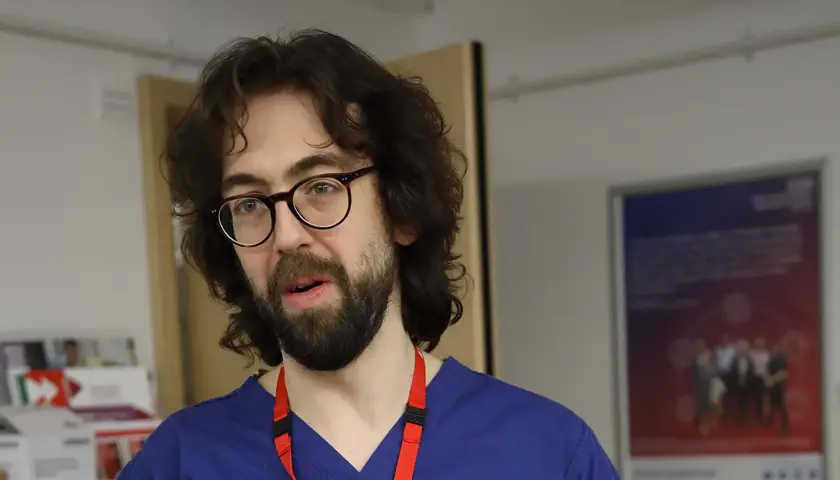

Ed Hiller, a general medical consultant and GP who works at Watford’s virtual hospital, says virtual wards can offer greater continuity of care than most hospital treatment as they allow clinicians more time to monitor symptoms, signs and medications to gauge how a patient is recovering in what he calls ‘sub-acute care’.

‘A couple of days in hospital doesn’t give the full clinical picture,’ he says. ‘In hospitals, people get labelled as “this condition” – and everyone knows the standard treatment for “that condition” – but there might be more complexity. And they might never know if what they did was successful. Having that wider arc [by monitoring patients virtually] helps avoid readmissions and gives people joined-up holistic care.’

Dr Keenan reports ‘huge success’ in early discharges of patients who have, for example, lung cancer and pneumonia, with ‘really moving’ feedback. Through virtual wards, he notes ‘patients say it’s a much softer landing in the community’.

There are a lot of natural anchors at home, understanding where they are, how to move around

Dr Ed Hiller

‘Case finders’ are tasked with identifying hospital patients who might benefit from moving on to a virtual ward. Patients, or their next of kin, must consent but Dr Rochford says refusal is rare. He also notes instances of consultants asking the virtual ward team to assess patients who have self-discharged but they would like to keep in. GPs sometimes call with concerns about patients who refuse to go to hospital despite advice to do so, who Dr Rochford says can often be monitored appropriately on a virtual ward which ‘gives them their biggest opportunity to stay at home’.

Dr Hiller says going into hospital ‘can be very upsetting’, especially for a confused patient. He explains: ‘There are a lot of natural anchors at home, understanding where they are, how to move around, keeping their independence. In hospital, they can get upset and delirious. Is that the best environment for that patient? Most frail patients do better at home. They know where everything is, if you take them out of that environment it might be more difficult.’

Back-up plans

Dr Rochford says virtual wards offer a ‘wrap-around service’ with hospital-level care and a long-term plan. He notes the ability to escalate is there if needed but says this is rare because of ‘constant conversations’ with hospital consultants who ‘really value’ the service.

In the acute virtual ward, teams are constantly monitoring patients’ vitals. If, for example, oxygen levels become low, the system alerts them.

In that instance, someone calls the patient and a community nurse may visit. They might then need a face-to-face assessment or scan at hospital, which can be arranged on a priority basis, and can be brought in urgently in an emergency – although Dr Keenan says this ‘very seldom’ happens.

Patients and carers are urged to deal firstly with the virtual-ward team – which in Watford operates from 8am-6pm seven days a week – but can always call 999, 111 or their out-of-hours GPs. For this reason, some GPs had concerns about how this might affect their already considerable workload when NHS England announced plans to expand virtual ward beds.

Drs Keenan and Hiller say in practice it is rare patients would contact their GPs, as they are in such regular contact with virtual ward teams that it is the natural point of contact. Dr Rochford says GPs find virtual wards ‘reassuring’ despite ‘naturally having concerns’ when they launched.

‘GPs have been crying out for the support to manage these complex patients for years,’ he says. ‘For the first time, there’s an answer. These patients are complex and frail, they need an MDT both short-term and long-term – not just one person.’

The advent of shared care records, Dr Rochford says, makes the process transparent for GPs. ‘The patient is our patient throughout,’ he adds. ‘GPs can see what we’re doing – so we don’t need to bother them with questions, and they can check the notes if they get a call.’

A similar collaborative approach is intended with partners in social care too – as some Hospital at Home patients may be living in social care environments. Bridging services can help social care residents being treated on virtual wards, and sometimes virtual ward staff help carers with those patients’ needs.

Erin Gallagher, a frailty nurse consultant who visits patients in the community, draws on her previous experience in acute and community settings for her role.

She says families and carers ‘put a lot of trust in us’ so ‘it’s important not to overwhelm them’. ‘We’re here to deliver specialist support, but we’re also mindful that we're entering people’s homes,’ she says.

Ms Gallagher feels the level of care at home is better because ‘you’re spending more time with a patient, not running around a busy hospital’ and describes the role as the medical team’s ‘eyes and ears’ on the ground.

Part of the nurses’ role is to show patients and carers how the technology works. This is usually done the day before they go home if it is an early supported discharge. Support is always there for questions. If patients don’t have capable smart phones they are given tablets, connected to a phone signal so those without WiFi can still benefit. Patients open an app and attach their monitoring devices which send recordings to the hub, then answer questions about how they are feeling. If this isn’t completed an alert is sent to the hub.

Heart failure and COPD patients receive ‘more tech-heavy’ treatment, explains Dr Keenan, who emphasises: ‘This is about the patient, not about the tech.’

As many patients are older adults, he says there is always a manual alternative option – with some observations taken over the phone and others from visits.

Dr Rochford says the technology involved ‘is becoming very, very good’ after initial ‘teething issues’.

From a clinician’s point of view, he says: ‘Historically, you only had a stethoscope, your eyes and your hands to make a decision. You might feel the best place for the patient is at home but you don’t have all the information. The tech is improving to level us up more to what the hospitals are offering.’

Using the example of blood testing, he explains: ‘We can take a tiny vial of blood, put it into the machine and it will give you quite a lot of the results you would get in hospital. With that information you can make a really informed decision.’

Dr Hiller says ‘this is technology that not many people are using’ and while he notes it ‘can still be better’ (he would like to see smart watches) the virtual ward as a relatively new model is able to ‘drive technological changes’.

Recruitment plan

While the wards themselves are virtual – they still need to be staffed. NHS England’s proposals require recruiting for 8,500 roles, something critics say is difficult in an already acute workforce crisis.

Dr Rochford acknowledges ‘the workforce crisis isn’t going away’ but says surveys show staff empowerment and greater levels of retention in virtual ward teams.

Dr Keenan says the virtual hospital in Watford is focused on broadening its workforce and has started employing clinical fellows and senior house officers to support its consultants and GPs.

‘It’s important we train new doctors across acute and community so they can do both, then that holistic model will develop over time,’ he says.

Dr Hiller says that, as an early adopter, the Hertfordshire virtual ward team has been able to ‘build the road in front of us’ and the next challenge is ‘how to expand while keeping it clinically relevant’.

This is about the patient, not about the tech

Dr Niall Keenan

Doctors running the virtual wards agree with Mrs Kaye it takes time for patients to get used to the idea of hospital-level care in their homes. The same goes for doctors.

‘There is a bit of a mentality change about what happens in hospital and what happens outside hospital,’ says Dr Keenan. ‘A lot of doctors feel it’s perfectly fine to have a patient sitting in a hospital bed waiting for a blood test in two days’ time, we feel that is not acceptable.

‘Patients very rarely challenge that, but they should. Why can’t they have that blood test at home in two days’ time? This idea is to try and deliver that for people.’

- Until September 2024, resident doctors were referred to as ‘junior doctors’ by the BMA. Articles written prior to this date reflect the terminology then in use