A hostile environment?

Doctors have come from across the world to work for the NHS – it is often said there would not be an NHS without them. But many international doctors have felt an increasing sense of threat, fuelled in part by the toxic debate over immigration. Peter Blackburn reports

‘In the beginning I felt very welcomed. Very supported. People were curious and accepting. You felt your role in the NHS was appreciated because there were shortages of staff.’

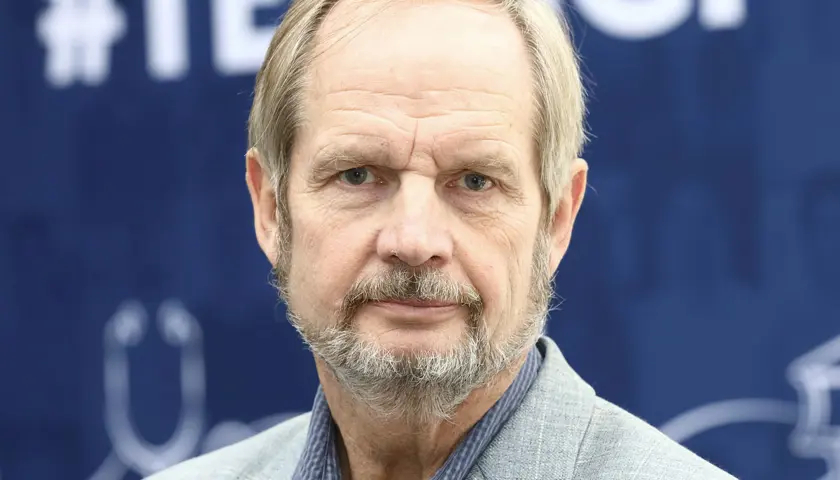

These are the words of a doctor who come to the UK from Germany more than 20 years ago. A surplus of doctors in his home country meant it was virtually impossible to find a way into popular specialties like paediatrics, and having done the equivalent of house jobs he came to the UK.

‘During that time a lot of people went to the UK, or to Switzerland, Denmark and Norway or the USA,’ says the doctor, whom we will call Dr Muller because the immigration debate has reached such levels of toxicity that he fears there will be a backlash.

‘The system in Germany then relied very heavily on relationships – the training posts were very starved and it helps a lot if you have family relationships with the professor or are coming from a medical family to get there. I don’t – I was the first doctor in my family.’

After around six months with no luck finding a job, Dr Muller came to the UK through an agency actively recruiting German doctors. He came with his wife, who is east Asian.

Aside from very rare occasions – particularly during heightened moments like football tournaments and an England versus Germany game where there might be songs about the war or similar incidents, most of which struck him as ‘playful’ – he felt welcome. It remained that way for years.

Dr Muller traces when things eventually began to change.

‘Definitely in the run-up to Brexit,’ he says. ‘Maybe from 2008 or 2009 and with lots of Eastern European doctors coming to the UK. People came from Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic and they were actually seen far more negatively. I noticed the difference from how I was seen and I found that quite unfair. They were as educated as I was and they were doing great jobs, not worse than I did. But I started to feel the public starts to turn against the EU and its countries including Germany.’

Blame culture

Trinidad-born vascular surgery specialty trainee Lisa Rampersad came to the UK in 2014 after meeting her partner, a UK national, while at medical school in Guyana and faced all sorts of difficulties settling and beginning work, including a two-year legal battle over the status of her visa.

When she eventually started work, she felt ‘thrown in at the deep end’, unfamiliar with working practices, the structure of systems, and even the everyday language used in the health service. She and other international doctors told The Doctor about their experiences earlier this year, and she also appeared in a podcast.

Wider society also presented some small obstacles, like local communities where people were less visibly friendly and chatty than those in the Caribbean, for example.

Dr Rampersad has faced down some issues around attitudes to people from abroad in the NHS, too.

She says: ‘I have noticed since working in the NHS that there are people who have things to say about IMGs or nurses, whoever. People from foreign places get looked at or get comments made about them quite often. There was a time when you would think a lot of this is older people where the comments are of their time – you can’t really change the language of somebody who is 90 years old.’

But Dr Rampersad says where those sorts of experiences might previously have been forgettable due to the ‘camaraderie’ and ‘togetherness’ of the NHS, much of those things have been eroded.

She says: ‘A lot of things changed from COVID and I can see it within the cohort working below me that they don’t have that same sense of hanging out with each other. It has helped feed into the sense of division we see now… you just see people as somebody at work. In the current political climate everyone looks for someone to blame – you’re hearing more and more from colleagues about these IMGs coming here, that they don’t speak English and it really grates on you.’

One doctor, who came to the UK from the Middle East and speaking on condition of anonymity to protect him from reprisal, says growing negative attitudes around immigration have become pervasive in society and the NHS and settling here is hugely difficult.

He says: ‘I’ve moved countries, lost my support system, lost family and friends, and all of my connections and networks that I spent nearly 30 years of my life building were gone overnight. If the roles were reversed and a UK doctor came to my home country they would find such hospitality. They understand that you’re new and you need support and to be taken care of.

‘Here, they’re not at work to be friends. You just fill a rota gap. And in wider society making friends is hard because British people don’t seem to want to involve me in activities or get to know me.’

If the roles were reversed and a UK doctor came to my home country they would find such hospitality

A doctor originally from the Middle East

The doctor, who works on the south coast of England, and has been in the country for seven years. adds: ‘The workplace is reflecting wider society. Everyone keeps themselves to themselves. The stereotype of British people being polite and respectful and queuing is nice, but everyone stays in their own bubble. It’s very isolating and individualistic.

‘I think people end up working with different ethnicities and people with belief systems that are being purposefully smeared in the media and fearmongered against. You don’t check that information or get over it in the workplace because you’re not allowed to talk about those types of things. People just retain the fears and there’s a lot of tension. The media is doing a good job of dividing society.’

For Dr Muller, recent years have meant ‘complicated’ application processes for citizenship, applying for passports for his two children – both born in Britain – and growing concerns about what the future holds in a country where tensions around immigration seem to have increased.

For him, the prime minister’s speech in May – where he said Britain risked becoming ‘an island of strangers’ without tough curbs on immigration, eerily echoing Enoch Powell’s infamous 1968 ‘rivers of blood’ speech in which Powell described white Britons as becoming ‘strangers in their own country’ – marked the moment where his fears really began to crystallise. He had thought the years of Conservative rule might have been the height of scepticism about immigration.

‘The language that was used… horrifies me. The kind of expectations that migrants have to assimilate.’

Uncertain status

Peter Burke is a GP who was born in Ireland and qualified in 1978 after studying in Dublin, coming to the UK in 1982 when competition for GP posts across the Irish Sea was particularly intense. He agrees with Dr Muller: ‘I’ve been disappointed in Keir Starmer because he has too frequently followed the Conservative line and is clearly looking over his shoulder at the threat from Reform. I think that is a mistake and his speech about strangers was a mistake.’

Dr Muller adds: ‘They don’t want pockets [of society] where migrants can retain part of their culture. There’s this expectation that we become somewhat more British than the British.

‘It is quite familiar because this is how Germany often thinks about migrants. Germany has this idea of German as the leading culture, and people who come there are expected to assimilate to that lead culture. But I think that is wrong. Having been an immigrant for most of my life now I think it’s a matter of tolerance and respect and what we can learn from other cultures. And yes, we integrate, which means we accept systems and learn language where we can but we have an identity as well.’

Dr Rampersad says: ‘It’s the easiest thing for the Government to do – to say it’s not us, it’s these people coming here. And they’ve done a masterful job of it.’

In the weeks after Mr Starmer’s speech – which he has recently suggested he regrets, saying he should have read it more carefully, and ‘held it up to the light’ a little more – rumours and news stories about tightening of immigration laws swirled. Dr Muller became concerned about whether minor crimes or things like parking tickets would become a threat to immigration status.

He says: ‘Could my status here be terminated much quicker than I think? I probably need to get a British passport just to feel safe in this country and have my status secured and not have to live with the fear of being… thrown out.’

Politicians or the country should embrace migration as something that makes our lives richer

Peter Burke

The doctor from the Middle East adds: ‘I’m now actually worried about my safety and the safety of my future family if I was to raise one and remain in the UK.’

For Dr Burke, who says he was ‘very aware’ of the “no dogs, no blacks, no Irish” recent past of the UK when he came over in 1982 and felt the impact of The Troubles prejudiced some people when he arrived, some of the changes in attitudes in society of recent years and the mirroring of those from politicians might be the result of consequences of the decision to leave the EU which were not advertised by those selling the benefits of Brexit – immigration hasn’t been significantly decreased and an NHS which needs staff is still reliant on people from overseas.

He says: ‘We had huge benefits over the years of EU membership… I think EU staff greatly enriched the NHS. Brexit has been challenging because, among other things, it has largely cut off a supply of doctors. For EU nationals getting to work in the UK can be daunting. The net effect of Brexit has been a massive increase in immigration from India, Nigeria, and other countries. Although personally I welcome this, I am not sure it was a consequence that most Leave voters foresaw.’

Dr Muller has one key message after so many years in this country. He says: ‘Politicians or the country should embrace migration as something that makes our lives richer, our culture richer, that benefits the economy. Britishness is not something monolithic, it has always been a mixture of various cultures... why should that stop?’